At a family wedding earlier this month, an uncle was salivating over the prospect that the Vivus Inc. drug Qnexa could soon become the first in a new generation of obesity drugs to gain FDA approval. He needed to lose 50 pounds, he confided, and the drug seemed the answer to his prayers. Since we’ve written extensively about obesity and these drugs in BioWorld Today, he wanted my opinion.

At a family wedding earlier this month, an uncle was salivating over the prospect that the Vivus Inc. drug Qnexa could soon become the first in a new generation of obesity drugs to gain FDA approval. He needed to lose 50 pounds, he confided, and the drug seemed the answer to his prayers. Since we’ve written extensively about obesity and these drugs in BioWorld Today, he wanted my opinion.

I politely inquired whether he had considered dieting and exercise, which could produce similar results without the potential side effects of a prescribed drug – especially one in a category that’s been dogged by cardiovascular risks.

“That’s just too hard,” my uncle replied, with a mixture of helplessness and disdain.

Sadly, that’s exactly the attitude parents seem to be passing on to their children, and the results have been catastrophic.

Last week, the journal Pediatrics published Prevalence of Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors Among U.S. Adolescents, 1999-2008, which provided a sobering look at the twin epidemics of obesity and diabetes in teenagers.

Authors Ashleigh L. May, MS, PhD, Elena V. Kuklina, MD, PhD, and Paula W. Yoon, ScD, MPH, of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta concluded that obesity in the teenage population was unchanged, with one in three adolescents between the ages of 12 and 19 officially overweight or obese, with a body mass index of 25 to 30 or greater than 30, respectively. That figure is shocking in its own right.

But the horrifying change was a doubling in the prevalence of prediabetes and diabetes in teens over the same period, from 9 percent to 23 percent, along with cardiovascular disease risk factors formerly seen only in adults.

Really, parents? What part of this picture do you not understand?

Diabetes is a devastating chronic condition that can cause life-changing complications such as nerve damage, blindness, amputation, kidney damage, heart attack, stroke and, of course, death. And unlike the pounds that can be shed from an overweight teen, diabetes is irreversible and incurable. It’s a life sentence.

What’s the best prevention for Type II diabetes, which results from lifestyle factors and accounts for more than 90 percent of cases of the disease? Not a pill or a shot, but simple exercise and a diet that maintains normal body weight.

No right-minded parent would push their child in front of a moving train, but that’s exactly what many parents are doing when it comes to the health of their children. It’s hard – but not too hard – to fix that. Trust me. I raised two teens and I’ve heard all the excuses.

For starters, get them off the couch before their only muscles are located in the fingers that do their texting. Make them walk the dog, cut the grass, take out the trash and ride a bike. Even better, encourage them to play soccer, swim, or run track. I started jogging at the age of 40 with my 12-year-old daughter, who wanted to make her middle school basketball team. It’s turned into a family pastime.

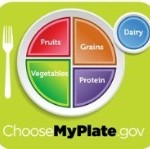

Substitute milk or water for soda. Treat French fries as a luxury instead of a staple. Give them carrots and celery – without the dip. Contrary to popular belief, fresh vegetables are cheap and don’t require a culinary degree to prepare. The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s ChooseMyPlate.gov offers simple tips for healthy eating on a budget.

And while you’re at it, take the same medicine, because children are smart. They watch their parents sit on their smartphones, upsize their burgers and guzzle their mocha Frappuccinos, and believe those habits signify adulthood. Instead, many children are slowly being steered into a lifetime of blood sugar monitoring, special diets and medications – and that’s if they’re lucky enough to avoid the more dreadful complications of diabetes.

Which brings me back to my uncle. It’s one thing for a 60-something adult to pack on 50 extra pounds and become a ticking time bomb, all the while hoping the approval of Qnexa, Contrave or lorcaserin will avert an explosion. It’s quite another for an adolescent to face the same potential fate.

Parents need to step up to the plate, and make it a healthier one, at that. The future of our children is too important to abdicate this responsibility to ignorance or indifference.